From My Bookshelf: Leon Blum’s “Lettres de Buchenwald”

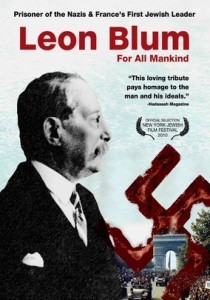

Thanks to my academic background in modern French history, I was delighted when the Generations of the Shoah International (GSI) Book/Film Discussion Group announced its December 2012 guests: Jean Bodon and Antoine Malamoud, who would discuss the documentary Léon Blum: For All Mankind. Bodon directed the film; Malamoud is Blum’s great-grandson.

Thanks to my academic background in modern French history, I was delighted when the Generations of the Shoah International (GSI) Book/Film Discussion Group announced its December 2012 guests: Jean Bodon and Antoine Malamoud, who would discuss the documentary Léon Blum: For All Mankind. Bodon directed the film; Malamoud is Blum’s great-grandson.

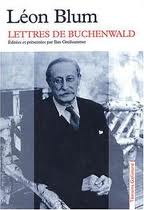

I was familiar with much of Blum’s story, especially his status as France’s first Jewish premier, most remembered for leading the Popular Front that came to power in 1936. But the fine documentary—which I was able to watch easily through Amazon Prime; you can also find it on Netflix—covers one piece of Blum’s story that I am ashamed to admit I did not recall clearly at all: Blum was arrested by the Vichy government in 1940 and imprisoned in France for nearly three years, after which he was transferred to German custody. In April 1943, he was moved to a detention site just outside the main camp at Buchenwald, where he remained until 1945. When Antoine Malamoud pointed out that letters that Blum wrote from his German detention to his son Robert (Malamoud’s grandfather, who was a French prisoner-of-war in Germany at the time) have been collected and published, as Lettres de Buchenwald, I was intrigued.

When I obtained a copy of the book, I appreciated especially the foreword by Malamoud himself, as well as the introduction by editor Ilan Greilshammer. The context they provide is essential. In fact, readers are likely to learn much more history from the contributions of Malamoud and Greilshammer than they will from the letters.

Particularly knowing now exactly what was happening within the camp, some readers may find it simply astonishing that Blum (and his beloved companion) led the existence that Blum describes in his letters, which essentially chronicle the weather, meals, reading material, and music. Blum provides frequent updates about his own health and his companion’s migraines. His repeated concern for the well-being of his son and daughter-in-law touched me, as did his interest and pride in his granddaughter (Malamoud’s mother) who spent those years studying in Switzerland. But some readers may find the letters banal, even self-centered. (Perhaps thanks to to my own dissertation, which focused on some “golden prisons” in which diplomats and consular officials were held during World War II, I’m slightly less stunned by this kind of “special” detention. But Blum’s Jewishness adds another, quite different ingredient here.)

Without doubt, Blum had to be mindful of his guards and censors. But unfortunately, there’s little in these letters that is historically compelling or especially insightful. One notable exception: a letter evidently intended to provide Robert Blum with instructions to follow should the father not survive his captivity. The letter focuses far less on the handling of material possessions than it does on how Blum wished his intellectual and political legacy to be maintained. Reading between the lines, I surmise that Blum wrote this letter after the death of his friend and fellow detainee, Georges Mandel. Overall, the letters are likely to interest those who seek to expand their knowledge of Blum far more than those who wish to learn more about Buchenwald.

A concluding note: The series of GSI Book/Film Discussions will continue throughout 2013. Yours truly will be the guest for the month of March, discussing Quiet Americans. To help prepare for this exciting “event,” I’m offering two more copies of Quiet Americans to be distributed through a Goodreads giveaway. Additional details about the GSI group and its 2013 guests are available here.

Thank you for posting this and writing so lucidly about Leon Blum and his times.

Thank you so much, Barbara.