(Interview conducted by Erika Dreifus for the November 2016 issue of The Practicing Writer.)

(Interview conducted by Erika Dreifus for the November 2016 issue of The Practicing Writer.)

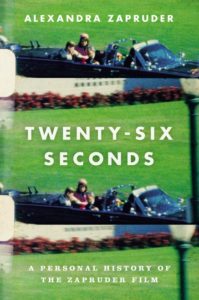

I knew Alexandra Zapruder’s name for quite some time before I met Alexandra in person a few years ago at an event in New York City. Like millions of other people, I knew the name “Zapruder” from the famous film footage of the Kennedy Assassination (I’d even mentioned it in one of my early short stories). But I became aware of Alexandra via acquaintances who worked at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington when she did, and then again when a friend we have in common asked me to inscribe a gift copy of QUIET AMERICANS to her. The moment I saw the PUBLISHERS LUNCH announcement about the deal for Alexandra’s second book, TWENTY-SIX SECONDS: A PERSONAL HISTORY OF THE ZAPRUDER FILM (out from Twelve Books in November), I began anticipating the opportunity to read it. And I’m so grateful that Alexandra was willing to answer a few questions about it.

Alexandra Zapruder began her career as a member of the founding staff of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. A graduate of Smith College, she earned her master’s degree in education at Harvard University in 1995 and returned to the Holocaust Museum in 1996.

In 2002, Alexandra completed her first book, SALVAGED PAGES: YOUNG WRITERS’ DIARIES OF THE HOLOCAUST, which was published by Yale University Press and won a National Jewish Book Award. She wrote and co-produced I’M STILL HERE, a documentary film for young audiences based on her book, which aired on MTV in May 2005. The film was awarded the Jewish Image Award for Best Television Special by the National Foundation for Jewish Culture and was nominated for two Emmy awards. Since 2005, Alexandra has worked as a freelance editor and writer on projects for young readers, teachers, and the general public.

Please welcome Alexandra Zapruder!

ERIKA DREIFUS (ED): This book is subtitled “a personal history of the Zapruder film.” And much of the book indeed details the extraordinary “life” of the images that your grandfather captured on November 22, 1963, when he stood awaiting the presidential motorcade with his home-movie camera–just as many of us who aren’t professional filmmakers might today seek to record a similarly public event on our phones. But you also provide another history: a biography of your grandfather Abraham Zapruder (1905-1970). Please tell us a little about him, apart from his identification with the film.

ALEXANDRA ZAPRUDER (AZ): Our grandfather was born in Imperial Russia in 1905 into a Jewish family of very limited means. He had three elder siblings: two sisters and a brother who was afflicted with a club foot. His father left Russia in 1909 to establish himself in the States, and his mother, Chana, essentially raised the children alone for the next 11 years until they were able to join him in America. At some point between 1915-1920, the elder son, Morris, died under unknown circumstances. Our grandfather was forever marked by the trauma that he experienced in Russia at that time.

In America, he worked as a dressmaker on Seventh Avenue and eventually struck out for Dallas, with his young wife and two small children, to make his own way in business and in life. He was a remarkably curious and inquisitive person, blessed with many interests and talents (music, fixing things with his hands, playing pool and golf, and amateur filmmaking) and known for a quirky and endearing sense of humor. There is much more that could be said about him, but suffice it to say that he was adored within our family (my brothers and I never knew him as he died of cancer when we were babies) and loved and respected in the Dallas Jewish and dressmaking communities.

ED: This isn’t your first book. You are also the author of SALVAGED PAGES: YOUNG WRITERS’ DIARIES OF THE HOLOCAUST. How did the experience of writing and publishing the previous book help you approach this project?

AZ: Not unlike having children, a second book can be inherently less daunting–no matter what challenges it presents–just because you’ve walked through the process once before. I wish I could say that I had been more organized in my research the second time around, or more methodical, or that I was smarter or faster or better. I’m afraid that’s not the case.

But there was one incredibly important thing I learned from SALVAGED PAGES that I applied to TWENTY-SIX SECONDS. I found that there was a long period during which I was reading, synthesizing, absorbing new information, struggling with framing and concepts, and generally feeling lost in a maze of facts, ideas, suppositions, impressions, reactions, and the like. For a long time, when I was working on SALVAGED PAGES, I assumed that I was confused because I was bad at thinking and writing, and that if only I were smarter or knew more, I wouldn’t feel that way. Or, to put it another way, I thought that I was struggling because I was, in some fundamental way, doing it wrong. Now I know that this lost and confused feeling is a critical phase of the thinking and writing. I’ve gotten a little better at trusting that dwelling in that mess is essential to finding the threads that I want to tease out. As something of a control freak, I find that this is incredibly hard. But experience helped me weather it better this time.

ED: TWENTY-SIX SECONDS required a staggering amount of research, including a daunting number of interviews. At one point, you write: “In time, I would become comfortable making cold calls, sending e-mails, and conducting interviews with Washington power brokers and lawyers, leaders in government, novelists, filmmakers, journalists, artists, scholars, and assassination researchers.” What advice can you offer for other writers who may also feel uncomfortable facing this sort of task?

AZ: This is a hard one. There’s really nothing to do but do it. Except in rare cases when people didn’t use email, I always wrote ahead so that I could explain exactly what I was doing, what my project was about it, and what I was asking from the person to whom I was writing. This helps a lot because it gives people time to think and respond, rather than catching them off guard by phone.

However you go about it, I think the most important thing is to be well-prepared, to know exactly what you are asking for, and to be incredibly polite. It’s amazing how far good manners will take you, especially when you are asking for people’s time, memories, experiences, and the like. I found that people were generally happy to be asked for their input, especially those who had a particular history or expetise that was germane to what I was writing. If you are on the receiving end of the question, you might only get asked it once in a lifetime so it can be gratifying to have a way to share what you know.

I also learned that a project like this depends completely on interviews of this kind. It reminded me that if people ask me to share what I know about a topic because they are working on something, and I actually have something to contribute, I should do everything in my power to say yes, no matter how busy I am.

ED: On a related note: Beyond the comfort factors, what specific tips–including recommendations for tools/technology to assist with recording, transcribing, etc. (such as what Don De Lillo evidently referred to as “the eavesdropping device” when you met with him)–might you offer?

AZ: I used a small hand-held audio voice recorder. It is nothing special–it just captures voice-to-voice audio–but it can be hooked up to the computer to download audio files and it’s so easy that even I can do it, which is saying something. After trying a few methods for transcription, (a friend did some, then a company), I found a transcriber named Gloria Thiede who charged a reasonable fee and worked fast and produced good, clear transcripts of my interviews. (I have a writer friend who transcribed his interviews himself which I think is admirable and smart, if you have time and patience to do it. I didn’t.)

In terms of preparation, I did my best to read whatever I could that was relevant to the interview in question, jot down specific notes and questions I wanted to ask, and mentally prepare myself for how I wanted to handle areas where the interviewer and I might not see eye to eye. The one thing I regret, listening to the interviews now, is that I didn’t hold my tongue more. It’s very hard not to treat an interview like a conversation. But if you learn to be silent and to hang on through the pauses, a lot more will come out. The interviews where I did that went better and contained more valuable insights. This is a lifelong process. I have a long way to go.

ED: Finally: Many of our readers may recognize your last name from still another context–you’re the sister of poet Matthew Zapruder. For anyone who may be new to *his* work, where would you recommend starting?

AZ: Actually, I’m the sister of TWO artists. Matthew is the eldest of the three of us, and he is indeed an extraordinary and accomplished poet. I love all of his books, but I especially loved COME ON ALL YOU GHOSTS (2010) and SUN BEAR (2014). He is writing a book titled WHY POETRY that is forthcoming in 2017. I also have a twin brother, Michael, who is a gifted musician and songwriter. He has several beautiful albums, including NEW WAYS OF LETTING GO (2006) and DRAGON CHINESE COCKTAIL HOROSCOPE (2012) and created an incredibly inventive collaborative poetry project called PINK THUNDER in which he set collected works by poets to music. He is now a composer of classical music, getting his PhD at University of Texas in Austin.

My brothers and I have a close relationship, and we share our work, our challenges, and our successes. Our friend Dini Karasik, who publishes a literary journal called ORIGINS, did a lengthy interview with the three of us about our family upbringing and how we think about our creative lives as individuals and together. I’m biased, but I think it’s a really special interview.

ED: Alex, thank you so much for your time, and congratulations on the imminent publication of TWENTY-SIX SECONDS.

To learn more about Alexandra Zapruder and TWENTY-SIX SECONDS, please visit the author’s website. My thanks to Alexandra Zapruder and Twelve Books for the complimentary advance copy that allowed me to prepare my questions.