“Raucous Family Memoir Meets Medical Adventure”: Q&A with Mike Scalise

“Raucous Family Memoir Meets Medical Adventure”: Q&A with Mike Scalise

By Erika Dreifus

(Editor’s note: A version of this interview was originally published in the February 2017 issue of The Practicing Writer.)

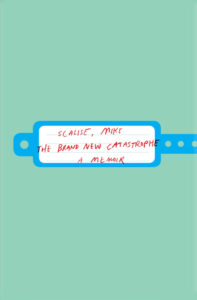

My memory is usually pretty good, but I honestly cannot recall when Mike Scalise and I began corresponding. In my recollection, we connected back in the early years of this newsletter; Mike wrote to express his appreciation. Eventually, we met “IRL.” I’m a big fan of Mike and his work, and I’m thrilled to be able to host him for a Q&A here this month, where we “talk” mainly about THE BRAND NEW CATASTROPHE, his new memoir just out from Sarabande Books.

Mike Scalise’s work has appeared in AGNI, INDIEWIRE, NINTH LETTER, THE PARIS REVIEW, WALL STREET JOURNAL, and other places. He’s an 826DC advisory board member, has received fellowships and scholarships from Bread Loaf, Yaddo, and the Ucross Foundation, and was the Philip Roth Writer in Residence at Bucknell University. His memoir, THE BRAND NEW CATASTROPHE, was the recipient of The Center for Fiction’s 2014 Christopher Doheny Award.

Please welcome Mike Scalise!

ERIKA DREIFUS (ED): This book is being advertised as “raucous family memoir meets medical adventure in a heartfelt, hilarious debut that explores the public and private theaters of illness.” Let’s begin with a brief explanation of the illness, shall we?

MIKE SCALISE (MS): Yeesh–here goes. The easiest way to say it is, “I’m a former ACROMEGALIC who is now HYPOPITUATARY due to a PITUITARY APOPLEXY.” What that means is, for a time in my early twenties, my body produced excess growth hormone due to a tumor on my pituitary gland (acromegaly) that I was unaware of. One night, that tumor burst in the brain (apoplexy!) which shorted out my pituitary gland entirely. So now my body doesn’t produce hormones at all (hypopituitarism). Each element of my condition isn’t terribly uncommon on its own. But the combination of them all, together, in one body, it is very rare. Which has been interesting.

ED: It seems to me that a challenge for many memoirists who write about illness is negotiating how to avoid having suffering and trauma overwhelm the narrative. THE BRAND NEW CATASTROPHE truly is enlivened by “raucous family” and “hilarious” elements. How consciously did you strive to avoid having pain and misery suffuse this memoir (as they very well might have)? What craft advice (or similarly “balanced” illness memoirs) might you recommend to memoirists facing similar challenges in their own work?

MS: Good question. I always had that balance in my life, even before my illness–the humor knocking up against the pathos, however you want to describe it. Which could be why I didn’t see my own story very well in the weightier, more forthright memoirs I read (and loved). Depictions of pain have a ceiling, at least for me. I could only figure out so many interesting ways to write “This hurt. I was very scared.”

Life moves at its own pace around that pain, and normal, daily humiliations encroach upon it, which I felt so acutely while I was going through all this stuff. Exploring that was far more interesting to me, and gave readers a more of an entry point than delving into the pain or fear may have. Your brain might be bleeding, but your breath can still be horrid enough offend people, too.

As for models, I’d advise memoir writers to hunt down “I didn’t know you could do that” books–works that give your story permission. I had a running rotation of memoirs, both prose and graphic, that managed that same balance you’re talking about in a way that surprised me, but also let me know it was okay to feel how I felt about my own story: Donald Antrim’s THE AFTERLIFE was a big one, but so was Philip Roth’s PATRIMONY, Julia Wertz’s DRINKING AT THE MOVIES, Susanna Kaysen’s GIRL, INTERRUPTED, Jeffrey Brown’s FUNNY MISSHAPEN BODY, and Deb Olin Unferth’s REVOLUTION. That last one kind of saved me.

ED: Please tell us a bit about the prize that this book has already won–the Christopher Doheny Award–and its role in publication with Sarabande Books.

MS: Christopher Doheny, from what I’ve learned, was a rare soul and staunch lover of literature who lived with cystic fibrosis into his thirties, which is a rare thing. After his death in 2013, a bunch of people who worked alongside him at Audible.com banded together with the Center for Fiction to start this award as a way to recognize stories about illness and family, but also to keep his memory and sensibilities alive. It’s hard to do justice to what a humbling honor it is to be associated with that effort. The more I learn about Chris, the more I think we would have been good friends.

As for Sarabande, they offered to publish THE BRAND NEW CATASTROPHE following the Doheny Award announcement in 2015, and if I get to talking about how wonderful its been working with them, I won’t stop, and it will become very, very obnoxious here in the interview. So I’ll just say its been the best professional relationship I have ever had and leave it there.

ED: Am I correct in assuming that your wife has already read the book? Have other family members and medical professionals depicted in the book read it yet? Tell us about their reactions?

MS: My wife HAS read the book, many times, over many years. She’s a pretty private person, and it hasn’t always been easy for her to have the raw parts of our life together open to everyone. But she’s been far more understanding, and generous, and encouraging with this process than she needed to be. Friends and family as well, which I have to say is surprising. It’s not a normal request, to ask someone to be A-OK with your version of their life, as they live it, in a book, for everyone to buy. No one should be okay with that, and some of my family definitely struggled with it along the way. I struggled with it too. My feeling is: whatever your response to being depicted in a memoir is, it’s the right one.

With my doctors who have read it, it’s sparked a really unexpected conversation, one I don’t think they often get to have with most patients, who they see for only about 30 minutes every few months. In some senses, the book presents a more detailed account of acromegaly, or hypopituitarism, and its been great to open that up to my doctors. We’ll see what happens with it, but so far so good.

ED: How is your health these days?

MS: Good! I’m actually healthier than I’ve been since this all happened (knock on wood). My medications have plateaued, I’m getting really strong care from my specialist, and I’ve been able to finally build the life my illness requires in a way that I’m happy about, which hasn’t always been the case. Work life is finally where it needs to be. Writing life is getting there. Life-life is a wild, maddening variable, but when won’t it be?

ED: Indeed. Thank you so much, Mike!

You can find THE BRAND NEW CATASTROPHE at http://amzn.to/2jeUF68 and http://bit.ly/2i78V0p. I’m grateful to Mike and to Sarabande Books for the advance galley that they provided me.