(This interview appeared initially in The Practicing Writer, August 2011.)

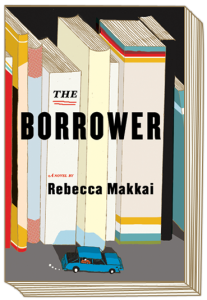

Rebecca Makkai is another writer I’ve been lucky to “meet” online. We connected several years ago on the Poets & Writers Speakeasy forum. Rebecca’s posts quickly earned her admiration and affection from the rest of the Speakeasy community. I’m just one of many Speakeasians who delighted in the news, awhile back, that Rebecca’s first novel had been bought by Viking. Now, Speakeasians and everyone else can enjoy this much-awaited, much-praised novel: The Borrower.

Here’s a brief description from the publisher:

“Lucy Hull, a young children’s librarian in Hannibal, Missouri, finds herself both a kidnapper and kidnapped when her favorite patron, ten- year-old Ian Drake, runs away from home. The precocious Ian is addicted to reading, but needs Lucy’s help to smuggle books past his overbearing mother, who has enrolled Ian in weekly antigay classes with celebrity Pastor Bob. Lucy stumbles into a moral dilemma when she finds Ian camped out in the library after hours with a knapsack of provisions and an escape plan. Desperate to save him from Pastor Bob and the Drakes, Lucy allows herself to be hijacked by Ian. The odd pair embarks on a crazy road trip from Missouri to Vermont, with ferrets, an inconvenient boyfriend, and upsetting family history thrown in their path. But is it just Ian who is running away? Who is the man who seems to be on their tail? And should Lucy be trying to save a boy from his own parents?”

This is a terrific book–I had a tough time putting it down–and I’m delighted to welcome its author for a Q&A.

Rebecca Makkai is a Chicago-based writer whose first novel, The Borrower (Viking, June 2011), is an Indie Next pick and has garnered rave reviews in O Magazine, BookPage, and Booklist (starred review) among others. Rebecca’s short fiction will appear in The Best American Short Stories this fall for the fourth consecutive year, and appears regularly in journals like Tin House, Ploughshares, New England Review and Shenandoah.

Please welcome Rebecca Makkai!

Erika Dreifus (ED): Rebecca, congratulations on the publication of The Borrower. It’s pretty obvious that this is not an autobiographical novel, but I’m going to go out on a limb and guess that libraries have nonetheless appealed to you for quite some time. What is your own first library memory?

Rebecca Makkai (RM): My very small elementary school didn’t have a library, and so we were allowed to walk down the block to the public library in groups of three or four with a special pass. The fact that my first memories of the children’s section are also my first memories of unsupervised freedom certainly has colored my lifelong relationship with libraries, not to mention this novel. That one was a small and cozy library (which I nevertheless firmly believed to be haunted), but as an adult I prefer libraries that are ancient and vast and storied. The main branch of the New York Public Library is perhaps my favorite… And I was even married in the Peabody Library in Baltimore, an old-fashioned model if ever there was one. I think I seek out that sense of hauntedness to match the feeling of mystery I once associated with my own first library: the hush, the possibility, the anonymity.

ED: I’m always reluctant to ask this question, but I can’t help myself: Where did the first idea spark for this novel come from?

RM: About ten years ago I first heard tell of the programs across America that exist to “pray the gay away” from both adolescents and adults. I was shocked on a personal and political level, but the storyteller in me was salivating. There is any number of stories I could have told around that idea, but the viewpoint that intrigued me most was that of an outside observer who wanted to help the child but had no right to. I thought about myself at age ten, and where I’d have gone if I ran away… and it instantly became a novel about libraries, about books, and about the stories we tell each other and ourselves.

ED: You are an accomplished story writer (okay, that’s an understatement–within the year, you’ll have had a story in Best American Short Stories for four years in a row) as well as a novelist. So I have to ask: When you come up with an idea, do you “know” right away that it’s destined to be a story rather than a novel (or vice versa)? What, for you, helps define the “right” form for a particular work?

RM: In this case, I knew immediately, because of the scope of the conflict, that it would have to be a novel. I hadn’t been fishing around for novel ideas at all; I just found the story, knew I had to tell it, and also knew that it would take about 300 pages to tell. My second novel, in contrast, which I’m working on right now, I thought for years was a short story. The only problem was that try as I might, I couldn’t get it under thirty-five pages. It was originally called “Gatehouse,” and I have about five different versions of it still saved on my computer, labeled things like “Gatehouse, shorter,” “Gatehouse, chopped,” and “Gatehouse, eviscerated.” I knew I didn’t have enough plot to make a novel, either… but I finally realized it could be one small part of a much larger story. I hadn’t been wrong, at first, to see it as a short piece – that’s all it really was – I’d just forgotten that I could think bigger.

In general, I think we all have the instinct to know how long a story needs to be. We make those decisions all the time socially, telling a story over coffee or at a party. We know what’s going to be a thirty-second anecdote and what’s going to take some setup and explanation. We ought to trust those instincts, not fight against them as I was doing with my current project.

ED: Among the many reading pleasures of The Borrower was, for me, the sophisticated clarity (and I don’t believe that’s an oxymoron) of some of the concepts on which the book seems to be based. And many times, these concepts are summarized outright, whether in grown-up discussions of America as “a nation of runaways” or in Lucy’s declaration (to Ian) that “It just shows that people should be allowed to be who they are. If they can’t, then they turn into nasty, sad people.” Did you intend to highlight the potential of children’s literature as a source for literature about “big ideas”? Did you intend to remind us of that beauty (which some of us may have forgotten the longer we’ve been away from those books ourselves)? Was there anything especially challenging about this aspect of writing the book? Please explain.

RM: That clarity wasn’t a conscious reference to the children’s literature that both Lucy and Ian love, but I do think children’s literature has a lot to teach all storytellers about what works and how to hold a reader’s attention. It’s generous, as a rule. A children’s author doesn’t sit down saying, “I’m going to write something just for myself, and if readers don’t like it, it’s because they aren’t sophisticated enough, and I don’t care about them anyway.” Not that I don’t enjoy more obscure and avant-garde works on occasion, but I usually want to be a bit more giving as a writer. And it felt right in this case that Lucy, as someone whose job it is to connect kids with books, would be a generous (if remarkably unreliable) narrator.

I loved making The Borrower referential to my favorite parts of the children’s lit canon, through pastiche, plotline, and direct mention. I could go on for pages about my reasons for doing so, but one reason was that I wanted readers to remember, vividly, the books that made them readers to begin with. I actually found being in that children’s lit echo chamber quite liberating, especially in the license it gave to make some of my peripheral characters larger than life and to create an improbable road trip arc à la The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

ED: Speaking of children: You’re a teacher. How old are your pupils, and how aware are they of your writing? Do they know about The Borrower? What’s their reaction? Similarly, what’s the reaction of your hometown library/librarians?

RM: My students are ages nine through twelve, and they’re excited that I’ve published a novel, but they know I don’t want them reading it till they’re in high school. I actually think it would be appropriate for smart middle schoolers as well, but I worry my own students would be shocked to see the few four -letter words and alcohol references in The Borrower if only because they came from me. I could see them going, “But wait, she put me out in the hall for swearing that once!”

The head librarian at my childhood library emailed me a couple of weeks ago. She was partway into the book, and remembered my name from the writing contests I would participate in as a child. She didn’t seem horribly offended, which is fortunate.

ED: Anything else you’d like us to know?

RM: I’ll offer this by way of writing advice: the problems of my early drafts didn’t become clear to me until I sat down to write my synopsis for the agent search. Synopses are always hard, but if you can get one done early in the process, it really helps you to think about overall structure, pacing, and meaning. If found myself, as I wrote the synopsis, adding in things that were not in the novel but that should have been. Then I went back and fixed the novel accordingly. It might not work for everyone, but on my second novel I made sure to do a short write-up just a few months in. I’m not wedded to what it says there, but at least it’s a roadmap.

ED: Thank you, Rebecca!

To learn more about Rebecca Makkai and The Borrower, please visit the author’s website. My thanks to the publisher for the review copy.