Friday Find: Post-MFA Fellowships

Here’s a goodie from our archive: a compilation of fellowship and writer-in-residence positions of particular interest to new/recent MFA grads. Enjoy, and have a great weekend!

Here’s a goodie from our archive: a compilation of fellowship and writer-in-residence positions of particular interest to new/recent MFA grads. Enjoy, and have a great weekend!

Just wanted to follow-up on my earlier mention of The Atlantic‘s latest fiction issue and point you to some of the work I most enjoyed and am still thinking about. You can access each piece here.

–“The Laugh,” a story by Téa Obreht (see also the interview with Obreht)

–“Furlough,” a story by Alexi Zentner (see also the interview with Zentner)

–“Eyes on the Prize,” an essay by Alice Sebold adapted from The Best American Short Stories 2009.

Have you had a chance to read the issue yet? What impressed you? Please share, in comments (but do recall that I will be on the Internet only intermittently this week and therefore it may take some time for your moderated comment to appear).

Congratulations to newsletter subscribers Adrienne Ross and Carol Bowman on their recent successes.

Adrienne’s essay, “Startling Epiphany,” took third place among prose submissions in this year’s Portia Steele Awards. And Carol’s story, “Repairing a Broken Doll,” appears in the latest Workers Write! anthology, Tales from the Couch.

As always, please remember that I LOVE hearing about successes that come your way via a discovery in our newsletter or on this blog. Please, please, share your good news, and let me brag about you!

Today is my nephew’s third birthday. Like his older sister, little S. gives me endless joy, love…and ideas to think and write about.

Today is my nephew’s third birthday. Like his older sister, little S. gives me endless joy, love…and ideas to think and write about.

As fortunate as he is, my nephew hasn’t had the easiest start. Perhaps his greatest challenge is childhood apraxia of speech (CAS). If you’re not familiar with this motor speech disorder, you’re not alone: I hadn’t heard of it before S. was diagnosed.

In the words of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, “Children with CAS have problems saying sounds, syllables, and words. This is not because of muscle weakness or paralysis. The brain has problems planning to move the body parts (e.g., lips, jaw, tongue) needed for speech. The child knows what he or she wants to say, but his/her brain has difficulty coordinating the muscle movements necessary to say those words.” (You can also learn a lot about CAS from the Childhood Apraxia of Speech Association. And I’ll refer you to this post on my sister’s blog for additional personal insights.)

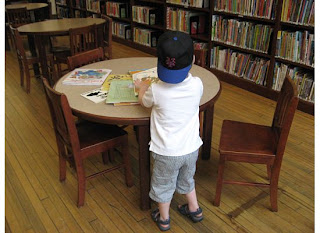

His language obstacles notwithstanding, my nephew is already an avid bibliophile (he’s pictured here on a recent library visit–photo credit courtesy of his mom). Children with apraxia of speech commonly encounter difficulties in learning to read, spell, and write as well as in learning to speak. So his road to full immersion in the world of words that means so much to me is likely to be significantly slower than I’d like it to be. At the same time, however, in these three years he has brought such added richness and joy to my life, and to the lives of all his family members (and, I daresay, to his dedicated therapists, who seem to find him as sweet and beguiling as we do!), that, despite all my degrees and publications, I can’t begin to describe in words myself.

Happy Birthday to my precious nephew, with my love always.

When I drafted yesterday’s post mentioning Abramson Leslie Consulting, the new firm offering services for prospective graduate students in creative writing, I had no idea about the storm that was brewing in the blogosphere around it. As I suggested in the post, there’s been controversy concerning similar ventures for prospective undergraduates. But I have to admit that the speed and intensity of the opposition to Abramson Leslie has surprised me. So I’ve been reading the objections as I’ve discovered them (for just a sampling, see the comment threads here and here). And I’ve been trying to formulate my own response, wondering why I did not react to the discovery of the new enterprise with the same vehement dismay so many others have.

My first reflection: Maybe I’m simply jaded. After all, I attended a high school where it was common for students to “train” locally with a private SAT “coach.” I worked with one. Would I have attained Harvard admission and National Merit Scholarship eligibility “on my own,” without the structure of my tutor’s assignments and the time I spent reviewing sample tests with her? Possibly. Was I too intimidated/crazed by the insane level of competition within the top stratum of my high school class to risk a bad test performance? Yes. Does the fact that I also had the transcript (four years of challenging coursework and high grades), recommendations, mini-essays and personal statement, and everything else that was required to confirm the test results and affirm the appropriateness of both the Harvard admission letter and the ultimate National Merit Scholarship award I received mean anything? I think so. But some might have doubts.

Then I thought: Maybe I’m simply less focused on the portfolio review portion of the services. That, after all, seems to be the aspect driving much of the online upset. Maybe my experiences are leading me to consider instead the broader array of services the new firm says it’s offering, like helping prospective applicants draw up lists of potential schools. Maybe I’m thinking of all the time I’ve spent responding to strangers’ e-queries concerning low-residency MFA applications/admissions. Brief exchanges I’ve sustained gratis, but if people really wanted my personalized response to their questions and my extended attention, I did charge for the service back when I was freelancing and adjuncting full-time. I can envision doing so again if appropriate.

And that is at least in part because it is established professional practice to do so. I do not see a difference, for example, between the consulting services for MFA applicants that are offered by respected organizations like Grub Street or the Sackett Street Writers’ Workshop and those from Abramson Leslie. Except, of course, for the fact that Seth Abramson (whom I do not know personally although we are both contributors to the second edition of Tom Kealey’s Creative Writing MFA Handbook) sure seems to have made a lot of enemies. And the curious situation that no one seems to be complaining as strenously about other organizations’ apparently higher fees.

Then, when I read protests about the products of consultations presenting inflated impressions of applicants’ inherent abilities, I recalled that my own MFA application submission was workshopped multiple times (and, horrors, even reviewed by a paid Grub Street consultant). Not, it’s true, because I wanted to polish it for the MFA application, but because I was seeking to perfect that first novel chapter for an agent/publication. So how representative of an applicant’s (my) inherent ability was that writing sample? How representative is any sample that’s been critiqued (and hopefully, improved) thanks to the paid work of trained, professional others?

There’s another point the anti-Abramson Leslie voices are making that I keep thinking about. It goes something like this: Abramson Leslie is “unethical” and “disgusting” (to cite two adjectives I’ve seen) because it’s not only morally wrong to give people who can and are willing to pay the fees a presumed advantage in this process. The endeavor will also lead to a sort of corruption of the (presumably, heretofore unadulterated) arena of artistic talent that is a graduate writing workshop and program, not merely because candidates will henceforth be admitted on the basis of work that isn’t really representative of their abilities, but also due to the tragic consequence that their peers will have to suffer through reading utterly abysmal original work when they could have enjoyed the gorgeous prose or poetry of someone more innately gifted—who didn’t (or couldn’t) pay for an application portfolio review.

Well, I hate to break this news, but in my experience, at least, the system just isn’t that pure. There is plenty of abysmal work being circulated in graduate writing workshops. And, again, for quite some time now, people have paid good money for other consultants, conferences, and workshops to improve their work (whether with the express intent of using the advice for graduate writing program applications or not).

I think, too, that those who are arguing against the portfolio review may not see it the way that I do. Based on my reading of the Abramsom Leslie Web site, for instance, I understand the consultants to be individuals who, as workshop teachers and other editorial consultants have done before them and will continue to do whether or not the new venture succeeds, will offer critiques and suggestions, not rewrites. If the client can’t apply the suggestions or think through questions the critiques raise, s/he actually isn’t going to be able to improve his or her work very much. And if s/he can, in fact, apply sound suggestions and engage with the critiques, maybe s/he is even more of an ideal candidate than one might have thought before the consultation began.

Finally, and with a bit of faith in the process, I am hypothesizing that someone who is truly unable to write poetry or prose at a level appropriate for graduate school may similarly lack a solid undergraduate transcript. Or strong recommendations. Or a satisfactory critical essay/GRE scores/statement(s) about herself or the books that have meant the most to her. I expect that someone applying to a graduate program in creative writing will present multiple qualifications in the application package. I am hoping that would-be graduate students in creative writing don’t waste the time they spend assembling these packages. Because if the writing sample truly were the only thing that mattered, there’d be no need for full applications in the first place.

But I hear the critics. Some of them I know, from other online discussions, at least. I respect them. I am still thinking about what they have to say. What say you?