Friday Finds for Writers

Writing-related resources, news, and reflections to enjoy over the weekend.

Writing-related resources, news, and reflections to enjoy over the weekend.

Have a great weekend, everyone.

Writing-related resources, news, and reflections to enjoy over the weekend.

Writing-related resources, news, and reflections to enjoy over the weekend.

Have a great weekend, everyone.

Thanks in part to the writers I follow on Twitter, the past week has brought plenty of references and reactions to “Sandwich Girl” and a certain Canadian author/professor. (Nope, not going to link to them.)

Thanks in part to the writers I follow on Twitter, the past week has brought plenty of references and reactions to “Sandwich Girl” and a certain Canadian author/professor. (Nope, not going to link to them.)

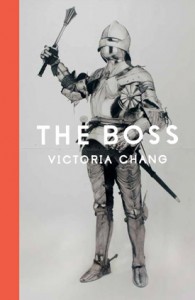

But I wish that I’d seen far more references to something else I discovered last week on Twitter (h/t @LMecham): a terrific and utterly refreshing interview on The Rumpus instead. For me, at any rate, Abigail Welhouse’s interview with Victoria Chang on the occasion of the publication of Chang’s third book of poetry addressed far more personally urgent and resonant concerns that I don’t see articulated often enough.

I encourage you to read the whole thing, but for the purposes of this post, I’ll share some selected quotations:

Abigail Welhouse (AW): “In my most perverse fantasies, everyone who isn’t me writes for hours a day….Also, they do all this while I’m at my office.”

AW: “There are narratives…that I hear repeated over and over about what kind of life constitutes ‘a writer’s life’—and working in an office full-time usually isn’t included in these stories.”

AW: “I recently attended a panel at the Slice Magazine Literary Writers’ Conference that ambitiously billed itself as ‘Life After An MFA’….The panel…consisted of five writers whose stories shared many similarities. According to the represented stories at the panel, the normal ‘life after an MFA’ seems to be this: write fiction or memoir, live in New York, and teach writing part-time.”

AW: “As a fellow poet who works in an office, I wondered how [Chang’s] full-time office work influences her writing—and I also hoped to figure out the secret to managing to write three books of poetry while working nine-to-five.”

Victoria Chang (VC): “I’ve always just liked writing poetry, but it’s much later that I’ve discovered that there’s this whole poetry world out there, that you almost have to be accepted into, like this little club. And it’s based on art, whether people like your work or not, but it’s also based on a lot of other things—geography, who you happen to connect with and where they sit in that ladder—and all of that felt really isolating and disheartening to me when I figured it out.”

AW: “Living in New York, I notice how easy it is to be doing what could be called ‘a writer’s life,’ while actually doing very little writing. Because you’re going to events, you’re talking to other writers, you’re doing all of this other stuff.”

VC: “Sometimes I wonder, though—I have friends that sit around and just write all day. And I think it’s the coolest thing. Imagine that: while they’re writing, and thinking, and dreaming, I’m on the phone constantly, and working, and running around like a maniac…and this or that. I don’t get that time, at all. But I wonder if that kind of lifestyle makes me—for me—a different kind of writer. I know I wouldn’t have been able to write any of these kinds of poems if I didn’t lead the life I led.”

VC: “I feel like I give myself all day long to other people and other things, and I still seem like I have something to write once in awhile. Not often, though. I haven’t written anything since this book was written two years ago, short of editing those poems here and there. That’s a new thing for me, because I used to think, I have to write every day.”

VC: “As a poet, I don’t sit around and say, ‘Oh, I want to write a book and get it published in the world.’ Anymore. I used to, when I was younger, when my goal in life was just to publish a book. As I published books, I realized, that’s not really what I want. I don’t care about the books as much anymore. I just want to write poetry.”

VC: “I was telling the poetry editor at McSweeney’s that if I never wrote a poem again, and never published another book, I really could care less. That’s just the phase of life that I’m in. I realize so much that it doesn’t matter. Yet, I’ve spent my whole life trying to do all this. Now that I feel like I’ve done these books and stuff, it just doesn’t appeal to me anymore. I could be one of those candidates that drops off the poetry world, and you never see me again, and I wouldn’t mind. Or, I could come back and write something in two years, or ten years.”

VC: “I’m not sure that I love being around [“the whole poetry world”] or in that. I love being part of poetry conversations. I love talking about what I’ve read. I regularly talk to poets, and it’s just like, ‘Have you read this?’ Me, being as busy as I am, I’ve read a lot more than most of the people that I know, except for one of my really close friends reads way more than I do. But, in general, I find that poets spend a lot of time thinking about themselves, and not a lot of time thinking about other poets, or other poetry. Unless they think about how it affects them, or how it could impact them.”

VC: “I love when I meet generous poets, and generous meaning nice people, who give to the poetry community, who do interviews, read other people’s books, and talk about them, spread the…love, I guess. That means a lot to me. It’s surprising—you don’t meet a lot of people like that. For the most part, it’s a world of artists that are very in their own heads.”

And a few reflections of my own: (more…)

Writing-related resources, news, and reflections to enjoy over the weekend.

Writing-related resources, news, and reflections to enjoy over the weekend.

Happy weekend, everyone!

Shabbat shalom!

Discovering that Jhumpa Lahiri was this past week’s “By the Book” interviewee in The New York Times Book Review was a delight. But discovering within the Q&A what Lahiri thinks about “immigrant fiction” was, I confess, something of a disappointment.

Discovering that Jhumpa Lahiri was this past week’s “By the Book” interviewee in The New York Times Book Review was a delight. But discovering within the Q&A what Lahiri thinks about “immigrant fiction” was, I confess, something of a disappointment.

In case you haven’t yet read the column, Lahiri was asked, “What immigrant fiction has been the most important to you, both personally and as an inspiration for your own writing?” Her answer:

I don’t know what to make of the term “immigrant fiction.” Writers have always tended to write about the worlds they come from. And it just so happens that many writers originate from different parts of the world than the ones they end up living in, either by choice or by necessity or by circumstance, and therefore, write about those experiences. If certain books are to be termed immigrant fiction, what do we call the rest? Native fiction? Puritan fiction? This distinction doesn’t agree with me. Given the history of the United States, all American fiction could be classified as immigrant fiction. Hawthorne writes about immigrants. So does Willa Cather. From the beginnings of literature, poets and writers have based their narratives on crossing borders, on wandering, on exile, on encounters beyond the familiar. The stranger is an archetype in epic poetry, in novels. The tension between alienation and assimilation has always been a basic theme.

Well, yes. And no. Cather’s My Ántonia appealed to me so strongly, on first and subsequent readings, because so much of it is about immigrants. Frankly, the same is true regarding my reception of Lahiri’s work. One of the local literary events I was most disappointed to miss this year was a panel–featuring Christopher Castellani, Ursula Hegi, and Julie Wu–on “the immigrant experience in novels.”

Yes, “many writers” originate from faraway places (or are only a generation or two removed from people who have). But as much as “the tension between alienation and assimilation has always been a basic theme,” it’s not omnipresent. What’s wrong with highlighting stories of immigrant experience? Why does Lahiri object to this perspective?

Reading Lahiri’s “By the Book” response on Sunday, I was reminded of one of my favorite reviews of Quiet Americans. I recall how deeply honored (and overwhelmed) I was when I first saw what the reviewer had written:

Dreifus’s clear, direct style and her subject matter bring to mind the stories of Jhumpa Lahiri. Both writers deal with immigrants to the U.S., the interaction of family generations, and the themes of pregnancy and birth. More than once I was reminded of Ashima in Lahiri’s novel The Namesake and her thoughts on living as a newly-arrived Bengali in America: “For being a foreigner, Ashima is beginning to realize, is a sort of lifelong pregnancy—a perpetual wait, a constant burden, a continuous feeling out of sorts. It is an ongoing responsibility, a parenthesis in what had once been ordinary life, only to discover that that previous life has vanished, replaced by something more complicated and demanding. Like pregnancy, being a foreigner, Ashima believes, is something that elicits the same curiosity from strangers, the same combination of pity and respect.” Dreifus and Lahiri both explore the out-of-sorts feeling, the interruption of ordinary life by the complications and demands of starting over in a new land, whether by choice or under compulsion. In Quiet Americans, Dreifus has made the extraordinary experiences of her characters accessible to readers who may feel they are far-separated from such events. As a good storyteller should, she shows that the feelings and experiences of the human heart are universal, regardless of the outer circumstances shaping each life.

I remain so grateful for that reviewer’s focus on what might connect my stories and Lahiri’s, and I continue to appreciate that for the reviewer, as for me, much of that connection rests in their shared status as examples of “immigrant fiction.” Even if, it seems, Lahiri might not be equally pleased.